|

| Edith Freeman Sherman, circa 1960. News-Sun photo. |

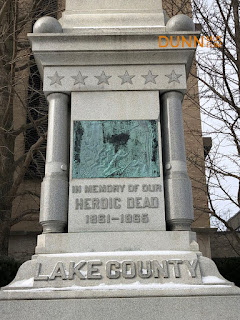

After the war ended in 1865, a Soldiers Monument Association was formed

to commemorate the war dead. It would take 34 years to raise enough money to

build a monument. Edith Freeman Sherman (1876-1970) was selected to create four bronze panels for the

base of the monument; panels depicted the county’s troops in the infantry,

artillery, cavalry, and navy.

Sherman was a talented sculptor and graduate of

the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. Her instructor in the Sculpture Department was American sculptor, writer and educator, Lorado Taft. Years later, her fellow alum considered her an "important sculptress" in Chicago.

One of her most prominent commissions was to create four bronze panels for the sides of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, which was erected on Waukegan's courthouse square in August 1899. In addition to her talent as a sculptor, her family's connection to the Civil War made her the perfect choice for the commission.

Edith Sherman's grandfather 1st Lt. Addison B. Partridge (1807-1888), and uncle Sgt. Major Charles A. Partridge (1843-1910) both served in Company C of the 96th Illinois Regiment. Her father, Isaac A. Freeman (1840-1923), served with the 1st Vermont Cavalry. Additionally, uncle Charles was the 96th Illinois' historian and chairman of the monument association. (For more info, read my post on Addison Partridge).

|

| Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Waukegan courthouse square. Dedicated August 29, 1899. Dunn Museum 61.8.88. |

Soldiers and Sailors Monument with one of Edith Freeman's bronze friezes. Photo D. Dretske, Dunn Museum.

Ninety-six years later, Lily Tolpo was commissioned for another Civil War monument.

|

| Lily Tolpo, circa 1960. Online. |

Lily Tolpo (1917 - 2015) was the eldest of five children in a Chinese-Polish American family. She learned to play violin and performed as a Vaudeville musician from 1935-39, before becoming a professional artist and sculptor.

Tolpo was commissioned to do a pair of bronze bas relief plaques to complete a project started by her late husband, Carl Tolpo (1901 - 1976).

Lincoln Monument west side of county courthouse, Waukegan. Photo D. Dretske, Dunn Museum.

|

| Lincoln monument by Carl Tolpo (1968), bronze plaques by Lily Tolpo (1996). Lake County courthouse, Waukegan. |

|

| Lily Tolpo with one of her clay models for the plaques. The image illustrates Abraham Lincoln's visit to Waukegan on April 2, 1860. Northwestern Illinois Farmer photo. |

According to Tolpo, she used her husband's concepts but rendered them "in another style more in keeping with the head [of the monument]." Her relief style captured "life-like reality and action."

|

| Detail from Lily Tolpo's clay model for plaque. Featured on the plaque are some of Waukegan's most prominent men: (left to right) Mayor Elisha Ferry, Samuel Greenleaf and Henry Blodgett. |

In 2014, the Bess Bower Dunn Museum (formerly Lake County Discovery Museum) received a donation from ArtbyTolpoartist.com of the molds for Lily Tolpo's bronze plaques, and the model for Carl Tolpo's Lincoln monument.

Nearly 100 years separated the work

of Edith Freeman Sherman and Lily Tolpo on the monuments. Both women were talented

sculptors and uniquely qualified to lend their artistry in commemorating Lake

County’s role in the Civil War.

On your next visit to Waukegan, take a stroll

around the courthouse to view the impressive monuments and the work of these

artists in person.