Edward Amet’s contributions to the early motion picture industry included the invention of the first practical 35mm motion picture projector—the Amet Magniscope—and the pioneering of special effects in motion pictures.

In last week’s post, I wrote about Amet’s wonderful Magniscope, which was completed in 1894 and ready for production in 1895.

This Magniscope, made by Edward Amet, was originally owned and operated by Arthur E. Johnson (1886-1974) during his career as a theater projectionist in Minnesota. It became part of the Dunn Museum's permanent collection in 2001, and is on exhibit in the museum's galleries. (BBDM 2001.12)

Magniscope advertisements stated it was "The perfect projecting machine. The Magniscope is simple, durable and compact, the pictures sharply defined and clear." The projector weighed about 90 pounds and the "model 1898" sold for $100. Since films weren't readily available, simply selling his invention to traveling showmen wasn't enough. Amet needed films to go along with the projector.

A traveling theatrical troop used the Amet Magniscope to show the first moving pictures in the Arizona Territory in 1897. For audiences accustomed to viewing color lantern slides, anything that moved was a wonder to behold on the screen. The first silent films were short—only 2 to 3 minutes in length—and featured circus parades, a winter sleigh ride, a horse-drawn fire department rushing to a call, and even prize pigs at the county fair.

A traveling theatrical troop used the Amet Magniscope to show the first moving pictures in the Arizona Territory in 1897. For audiences accustomed to viewing color lantern slides, anything that moved was a wonder to behold on the screen. The first silent films were short—only 2 to 3 minutes in length—and featured circus parades, a winter sleigh ride, a horse-drawn fire department rushing to a call, and even prize pigs at the county fair.

"Boxing Boys" featured Amet's brothers, Percy and Herbert, duking it out in a ring at the Scale Company in Waukegan where the Magniscopes were produced.

Like films produced by others, Amet's first films were straightforward recordings of movement, such as the "Boxing Boys," or his wife and daughter playing in their backyard in Waukegan.

Like films produced by others, Amet's first films were straightforward recordings of movement, such as the "Boxing Boys," or his wife and daughter playing in their backyard in Waukegan.

But quickly, Amet began thinking more in terms of each film having a theme or story to tell. His first "theatrical" films featured a marionette and tableau vivant (motionless performance in theater).

Still from "McGinty Under the Sea," the dancing skeleton.

Growing sentiment to free Cuba from the Spanish inspired this Amet tableau vivant "Freedom of Cuba" featuring Uncle Sam, Lady Liberty and little Cuba.

One of Amet's most endearing films was called "Morning Exercise" and featured two young women from Waukegan—Bess Bower Dunn and Isabelle Spoor (George Spoor's sister).

When the Bess and Belle arrived at the inventor’s home on North Avenue in Waukegan, Amet handed each a pair of boxing gloves. Bess Dunn thought she was doing “our town inventor” a favor. “We whipped those long skirts out of the way and had a fine old time.” For several historic minutes, the girlfriends punched each other while Amet took their picture with his camera, becoming the first women in motion pictures.

In 1909, while traveling in Spokane, Washington, Bess Dunn discovered that Amet had sold prints of the film. She was recognized by an usher of a local theater as one of the “boxing girls.” Amet’s film had traveled 2,000 miles and was still being shown 11 years later.

Amet's best known films are related to the Spanish-American War of 1898.

When war broke out, Amet allegedly sent a request to the U.S. War Department asking for permission to travel to Cuba to film the battles. His request was denied, but his enthusiasm for the idea did not diminish. He used accounts in newspapers to re-create the battles.

The land battles were filmed at Third Lake, a favorite fishing location of Amet. He enlisted his brothers and neighbors to be the actors. Shown are a still from the film, and the cast taking a break. Amet Collection, Dunn Museum.

The majority of Amet's work on the theme of the Spanish-American War presented challenges, since it was mainly a naval war. Amet made a series of films showing the naval battles in his backyard, including one titled “Spanish Fleet Destroyed” or “The Battle of Santiago Bay."

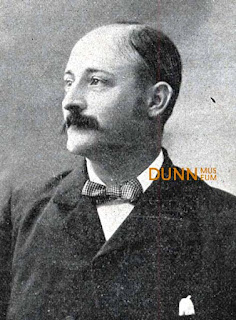

Edward Amet standing in his backyard with his set for the filming of "The Battle of Santiago Bay," 1898. (BBDM 61.33)

For "The Battle of Santiago Bay," Amet constructed a shallow water tank 18 x 24 feet with a painted backdrop of Cuba. Five or six of the important naval vessels in the battles, such as the USS Olympia, USS New York and USS Oregon were reproduced at a 1/70 scale in sheet metal, 3 1/2 to 5 1/2 feet in length.

The USS Olympia model built by Amet for the film as shown on exhibit in 2007. (BBDM 61.33.2) Photo © 2007 Jess Smith/PHOTOSMITH

The models were constructed with firing gun turrets, and smoking stacks and flags. The gunfire was replicated with blasting caps, and gunpowder and camphor soaked cotton wadding, which was electrically ignited and provided smoke for the ships’ smokestacks. All of these effects were controlled from an electrical switchboard off camera. Additionally, waves were created by underwater jets and a large fan off camera.

The models were constructed with firing gun turrets, and smoking stacks and flags. The gunfire was replicated with blasting caps, and gunpowder and camphor soaked cotton wadding, which was electrically ignited and provided smoke for the ships’ smokestacks. All of these effects were controlled from an electrical switchboard off camera. Additionally, waves were created by underwater jets and a large fan off camera.

Amet's artful use of special effects was so convincingly portrayed that he was asked to show his “war movies” at the opening of the Naval Training Center Great Lakes in 1911. Amet's "Battle of Santiago Bay" film (right)

The Spanish-American War was a popular topic in all sorts of media, including film. The American Vitagraph Company also made a version of the "Battle of Santiago Bay" in 1898, directed by J. Stuart Blackton. This film (rather than Amet's) is the one most often referenced in the history of early motion pictures, but it is a far cry from Amet's film with its pioneering use of special effects. Blackton's film features small wooden model ships in a bathtub with cigar smoke blown onto the scene by an assistant off camera. If Amet saw this film he probably rolled his eyes and laughed.

To be fair to Blackton, he was pivotal in the early years of the industry, and was among the first filmmakers to use the techniques of stop-motion and drawn animation. He is also considered the father of American animation.

Since most of Amet's films are lost, historians rely on published catalogues of films available for sale. These lists give us insight to the wide range of topics popular with motion picture audiences. Amet's 1898 catalogue listed (in part) the following films (50 feet in length, price $9.00 each):

"Passing of the Milwaukee Fliers on the C & NW Railroad" (train in each direction)

"Mamma's Pets" (old pig and ten little ones)

"Tugs Towing Barge"

"Clothes Race" (swimming contest in Lincoln Park)

"The Ducks" (seventy young ducks in a pond)

"Interrupted Tea Party on the Lawn" (comic)

"Chicago Fire Department Runs"

Amet left for California sometime after 1913, and continued working on motion picture devices. In the image above, Amet (left) is making a film using an early sound recording camera he invented.

For the museum's permanent exhibition on Edward Amet, the staff tracked down a copy of the "Battle of Santiago Bay" from the Killiam Collection* (distributed by Worldview Entertainment), which is probably the best source for silent film era movies. The collection was assembled in the 1960s by Paul Killiam through acquisition from the Estate of D.W. Griffith, and later, a large portion of the collection of Thomas Edison.

We ordered the film (sight unseen) and crossed our fingers that it was not Blackton's version. Thankfully, it was Amet's film, and all 20 seconds of it plays in the museum's galleries everyday to the delight of visitors.

Special thanks to Carey Williams and Kirk Kekatos for years of research on Amet and his contributions to the early motion picture industry.

*The Killiam Collection was sold and no longer exists. 10/28/19