One of the most significant, yet little known contributors to the early motion picture industry was Edward Hill Amet (1860-1948) of Waukegan.

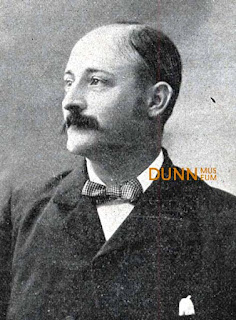

Edward H. Amet (1860-1948). Dunn Museum.

The Bess Bower Dunn Museum of Lake County maintains a collection of photographs, documents, lantern slides and objects related to Edward Amet and Essanay Studios.

This electrical engineer and self-styled “consulting inventor,” invented the first practical 35mm motion picture projector—the Amet Magniscope.

In the 1890s, electricity was not readily available. Amet’s Magniscope was operated manually by hand-crank and offered a choice of electric or gas illumination, allowing it to be used anywhere. In many ways, it was an improvement over Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope.

Edison's Kinetoscope was a motion picture viewing machine which used the 35mm film format, patented by Edison. Kinetoscope parlors were all the rage in major cities, but the machine allowed for only one person at a time to view moving images through a peephole. In 1894, Amet had seen the Kinetoscope in Chicago and was impressed, but not satisfied. Amet improved on Edison’s design by projecting images for all to see.

Photo of Kinetoscope parlor in San Francisco, circa 1895.

The Amet Magniscope's versatility made it the first practical 35mm film projector. Dunn Museum.

Amet's Magniscope used Edison's 35mm film format, and had gears which pulled film strips behind a lens at 32 frames per second, making the projected images appear to move realistically. The now familiar reel-to-reel arrangement, which Amet pioneered, was a significant step forward in film projection design.

According to George K. Spoor (1871-1953), while he was the co-manager of Waukegan’s Phoenix Opera House in 1894, Amet approached him for money to complete work on his “machine for the projection of motion pictures.” There is dispute among historians whether Spoor indeed gave Amet the money to start his business, but most agree that Spoor managed Amet's motion picture interests before moving on to found Essanay Studios in Chicago.

Spoor (third from left in bowler) discussing Amet's Magniscope with curious onlookers, about 1933. Beginning in the 1920s, there was a great deal of interest in Amet's work and in promoting Waukegan as the birthplace of motion pictures. Dunn Museum.

When Amet's projector was finished in late 1894, he acquired two discarded Kinetoscope films to show on his Magniscope. He cemented the films end-to-end and projected them against a wall in a factory building. “After the demonstration that night, there was not much sleep for any of us,” recalled George Spoor.

According to Spoor, the next day he bought 14 more discarded Edison films, and put out advertisements for the “Great Motion Picture Show” at Waukegan’s Phoenix Opera House at 10, 20 and 30 cents admission. They showed the films with Amet’s machine and made $400 the first week.

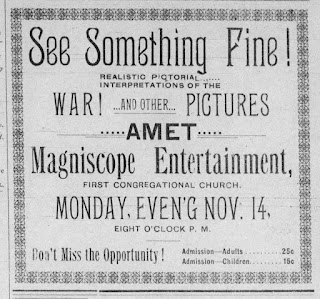

Advertisement to see Amet's motion pictures shown on the Magniscope at the First Congregational Church in Waukegan, November 14, 1898. Waukegan Weekly Gazette, November 11, 1898. Newspapers.com

It is generally accepted that the French Lumiere Brothers’ showing of motion pictures in Paris to a paying audience in the winter of 1895 was the beginning of the movie era. If Spoor’s memory can be trusted, and later accounts by Amet's brothers, the Magniscope showing pre-dates the Lumieres’ by one year. Waukegan newspapers from this period cannot be found adding to the rumors that Edison had them destroyed.

Amet's laboratory in the backyard of his property on North Avenue, Waukegan. This is where he developed his film and worked on his inventions. The building was razed in 1966. Dunn Museum.

From about 1895 to 1899, Waukegan became the center for the movie machine business as Magniscopes were produced at the Electrical Recording Scale Company and sold for $100 each.

Magniscopes were available to anyone without territorial restrictions, were manually operated, and did not require electricity as an illuminant source. Amet sold at least 200 to traveling showmen who were using lantern slides to entertain audiences, and who easily adapted to the moving picture format.

Amet is credited with at least 59 patents, including a musical instrument the “ethelo,” a guidance system for naval torpedoes (which he sold to the British government), a process for producing acetylene gas as an illuminant, and a fishing reel.

Remarkably, the Magniscope was not patented. Thomas Edison (1847-1931), who earlier had patented the 35mm movie film format, sued Amet and other inventors and entrepreneurs for using this film type. The results of the lawsuit meant that Amet could no longer manufacture the Magniscope. But with hundreds already in use, Amet was ready to move on to other inventions.

In 1957, Amet’s brother, Herbert (1880-1959), recalled that because of Amet’s improvements to the Edison Talking Machine, “Edison detested Ed with an undying hate. He had those gramophone patents.” Rumors abounded that Edison sent his thugs into towns to destroy any newspaper evidence of Amet's invention, in order to claim sole title to inventing motion pictures.

Herbert "Herb" Amet, 1898. Herb worked with his inventor brother, Edward, in the laboratory. Herb was a "player" in Edward's films, including in the "Boxing Brothers." 62.62.2, Bairstow Collection, Dunn Museum.

In 1907, George K. Spoor founded Essanay Studios in Chicago with cowboy actor / director G.M. “Bronco Billy” Anderson. Read my post on

Essanay Studios for more on that motion picture venture.

Amet left Waukegan around 1904, heading west and settling in California. He continued working on motion picture devices, as well as other inventions. When he died in 1948, he was working on a cure for cancer.

His obituary appeared in the

New York Times:

Edward Hill Amet

Redondo Beach, Calif., Aug. 17 - Edward Hill Amet, an inventor of motion-picture equipment, died at his home here yesterday. His age was 87. In 1895, Mr. Amet perfected the nagnagraph, known as the "grand-daddy of motion picture cameras." The first model of the camera is in the Smithsonian Institution.

The Bess Bower Dunn Museum acquired a Magniscope in 2001, which is on permanent display in the museum's exhibition galleries.

Amet home at 421 North Avenue, Waukegan.

Edward Amet's home at 421 North Avenue in Waukegan was built about 1840 and was the residence of Oliver S. Lincoln. The house is still standing and is part of Waukegan's Near North Historic District, which was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Amet's pioneering films will be discussed in next week's post. See my post

Amet's Films.