Mary Spoor Brand's illustration for Bobby and Betty With the Workers by Katharine Elizabeth Dopp, published by Rand McNally & Company, 1923.

The Golden Age of American illustration (1880 - 1914) gave women unprecedented opportunities to be employed as illustrators. The momentum it created would benefit Mary Louise Spoor Brand of Waukegan, who became a children's book illustrator in the first decades of the 20th century.

Mary Louise Spoor Brand (1887-1985). Ancestry.com volks1wag family tree.

Known as "Mollie" to her friends and family, Spoor was born on March 15, 1887 to Catherine Stressinger (1853-1947) and Marvin Spoor (1839-1927). Her father was an engineer for the North Western Railway, and except for an absence while serving with the 89th Illinois in the Civil War, Marvin Spoor ran a train between Waukegan and Chicago from the late 1850s until his retirement in 1902.

Growing up in Waukegan, Mollie was surrounded by creative individuals, including her family's neighbor, Edward Amet, who was an early motion picture pioneer and inventor. See my post on Edward Amet. Mollie's brother, George K. Spoor, partnered with Amet in the motion picture business. About 1895, George featured his eight-year old sister, Mollie, in a short film of her playing with ducks.

Mollie Spoor on her high school graduation day, June 1905, at the courthouse in Waukegan. Dunn Museum Collections.

In June 1905, Mollie graduated from Waukegan High School with "high honors" and was chosen class valedictorian for scholarship. Mollie was class treasurer and secretary of the school's drama club. The club's play that spring, "Hamlet," was held at the Schwartz Theater in Waukegan. Mollie Spoor starred as Ophelia alongside her high school sweetheart, Enoch J. Brand, who had the leading role as Hamlet.

Waukegan High School's Class of 1905. Mollie Spoor and Enoch Brand are noted with yellow stars.

Yearbook photo courtesy of Waukegan Historical Society.

Schwartz Theater in Waukegan where Mollie Spoor and her high school classmates presented "Hamlet" in 1905.

Photo 1950s. Dunn Museum Collections.

Photo 1950s. Dunn Museum Collections.

The Waukegan Daily Sun noted that "Miss Spoor has a peculiar ability in executing pretty water colors and drawings, but she has not made any decision as to what she will do in later life." Within a year, Spoor found a path to her future career and enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. There she excelled in illustration and portraits.

Mary L. Spoor's illustration featured in "The Art Institute of Chicago Circular of Instruction" for 1909-1910.

In 1907, Mollie's brother, George Spoor and actor/director "Broncho Billy" Anderson, founded a motion picture studio in Chicago. The studio's name—Essanay—was a play on the founders' initials "S and A." See my post on Essanay Studios.

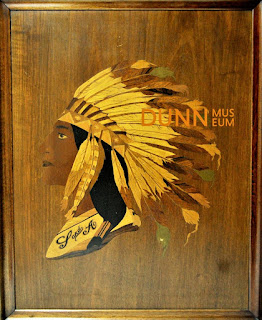

Mollie Spoor's inlaid wood design for Essanay Studio's logo. In 1961, she donated the piece to the Lake County History Museum

(forerunner of the Bess Bower Dunn Museum). 61.33.1 Dunn Museum Collections.

George asked his artistic sister to design the studio's logo. The distinctive choice of a Native American in headdress was likely George's idea, but the design was all Mollie's. Her framed piece was made of inlaid wood and hung in her brother's studio office at 1333 W. Argyle Street in Chicago.

In June 1910, Spoor graduated from the School of the Art Institute with honors. The Waukegan Daily Sun noted that "In every respect she is the ablest artist this city ever claimed... and has won honor after honor at the Chicago Institute."

Waukegan Daily Sun piece celebrating Spoor's accomplishments at the Art Institute, June 18, 1910. Newspapers.com

After graduation, she participated in a month-long Art Institute sketching class that went to the Eagle's Nest Art Colony in Oregon, Illinois. The colony was founded in 1898 by American sculptor Lorado Taft (1861-1936) and consisted of Chicago artists, many of whom were members of the Chicago Art Institute.

"Bye Bye Bunting" illustration by Mary Louise Spoor, 1917. Seesaw.typepad.com.

Mollie made her home in Chicago and her art career took off. Her skill and professionalism was in great demand in the Midwest's publishing hub, where she found work with Rand McNally, Lyons & Carnahan, and Congdon Publishers.

Jack and Jill chromolithograph by Mary Louise Spoor, 1917. treadwaygallery.com

Decades of technical advances in printing and the falling price of paper fueled the "ten-cent magazine revolution," spurring a demand for magazines such as the Ladies' Home Journal, and also children's books. In the late 19th century, books designed solely for children were brought on by the Industrial Revolution and a growing middle class with an awareness of the importance of preserving children's innocence and the benefits of play and amusement.

At the turn of the 20th century, a burgeoning demand for artists continued, and particularly for women artists as illustrators of literature targeted to women and children.

In the midst of this exciting time for illustrators, Mollie Spoor partnered with fellow School of the Art Institute student, Gertrude S. Spaller (1891-1970). The women became friends and colleagues, and worked together for ten years, even sharing an art studio in the tower of the Auditorium Building in Chicago.

Chicago Auditorium Building from Michigan Avenue. Spoor and Spaller's shared studio was located in the tower.

Photo by JW Taylor. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Spaller and Spoor illustrated children's readers titled, The Easy Road to Reading Primer, for Lyons and Carnahan of Chicago/New York.

The Easy Road to Reading, First Reader. This series was illustrated by Mary Louise Spoor and Gertrude S. Spaller.

Published by Lyons and Carnahan, 1919-1925. Seesaw.typepad.com.

Illustrations by Mary Louise Spoor for The Easy Road to Reading series published by Lyons and Carnahan. Seesaw.typepad.com.

Mollie Spoor also illustrated the stories of Katharine Elizabeth Dopp (1863-1944) for Rand McNally's Bobby and Betty children's books. Dopp was a notable American educator. The Bobby and Betty series featured the fictional children at play, at work, and in the country.

Mary Spoor Brand's illustration of "The Milkman and His Horse" written by Katharine E. Dopp for Bobby and Betty With the Workers, 1923.

During her career as an illustrator Spoor appeared under the name Mary Louise Spoor and after her marriage to Enoch J. Brand in August 1915, she was sometimes credited as Mary Spoor Brand.

In many ways, Mollie was ahead of her time as a career woman. Many talented women illustrators gave up their art careers when they married, a societal norm at the time. According to her wedding notice in the Waukegan Daily Sun, Mollie's art "services were in great demand" in Chicago, so much so that she postponed her wedding until she finished a project for Rand McNally.

Ten years after their high school graduation, Mollie Spoor and Enoch Brand wed in Waukegan.

Waukegan Daily News, August 11, 1915. Newspapers.com

Mollie and Enoch moved to Minnesota and then to Massachusetts for Brand's insurance work. Mollie temporarily set aside her career until her four sons were in school, and then returned to illustrating.

In 1922, the family came back to Illinois. They settled in Winnetka where Spoor became an officer in the North Shore Art League (est. 1924), and continued to express herself through her love of art until her death in 1985.

Mollie Spoor's illustrations charmed a multitude of children and parents in the early decades of the 20th century. Her skill as an artist contributed to children's illustrated books being respected as an art form. Today her work has received renewed interest as vintage children's readers have become collector's items.

Mary Spoor Brand illustration from Bobby and Betty with the Workers by Katharine Elizabeth Dopp for Rand McNally, 1923.

- Diana Dretske, Curator ddretske@lcfpd.org

Sources:

"Elect Club Officers," Waukegan Daily Sun, March 22, 1905.

"Earn High Honors," Waukegan Daily Sun, June 22, 1905.

"Miss Molly Spoor Wins High Art Study Honors," Waukegan Daily Sun, June 18, 1910.

"Mary L. Spoor Becomes Bride of Enoch Brand Here," Waukegan Daily Sun, August 11, 1915.

"Marvin Spoor Is Dead After Ailing For Over 25 Years," Waukegan Daily Sun, 1927.

"Enoch J. Brand," Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1948.

"Child Film Star' Mary Brand, 98," Chicago Tribune, October 31, 1985.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Circular of Instruction of Drawing, Painting, Modeling, Decorative Designing, Normal Instruction, Illustration and Architecture with a Catalogue for Students 1909 - 1910." Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1909.

- Smith Scanlan, Patricia. "'God-gifted girls'": The Rise of Women Illustrators in Late Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia." Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies. http://w.ncgsjournal.com/issue112/scanlan.html

- Goodman, Helen. "Women Illustrators of the Golden Age of American Illustration." Women's Art Journal, Spring-Summer, 1987, Vol. 8, No. 1. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1358335.

- Kosik, Corryn. "Children's Book Illustrators in the Gold Age of Illustration." IllustrationHistory.org.

- Kesaris, Paul L. American Primers: Guide to the Microfiche Collection. Bethesda, Maryland: University Publications of America, 1990.

- Dopp, Katharine Elizabeth. Bobby and Betty With the Workers. Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1923.

- Cowan, Liza, ed. "Artist: Mary Louise Spoor." SeeSaw: A Blog by Liza Cowan. February 7, 2012. https://seesaw.typepad.com/blog/artists-mary-louise-spoor/

Special thanks for research assistance to Ann Darrow, Librarian, Waukegan Historical Society www.waukeganhistorical.org; and Corinne Court, Senior Cataloging and Metadata Assistant, School of the Art Institute of Chicago.