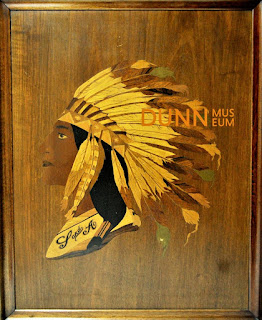

Photo 1950s. Dunn Museum Collections.

Friday, December 17, 2021

Mary Louise Spoor Brand - Children's Book Illustrator

Photo 1950s. Dunn Museum Collections.

Thursday, September 3, 2020

Flowers for Hull House

Guest post by Steve Ferrigan, Collections Digitizer for the Dunn Museum

When the Dunn Museum

staff were told to shelter in place back in March and work remotely,

one of the first things collections staff did was to take digital photos of diaries in the Minto

Family Collection in order to transcribe them from home.

It turns out you can learn a lot more than just about your own family by being cooped up at home for months. Sometimes you can learn about farm life in the early 1910s.

The diary I was tasked with transcribing was Susie Minto’s from 1912. Every once in a while, very rarely, something happens in a Minto Diary. Between the days listing who is working where and on what; between the small trips to nearby towns for supplies or new equipment; around the brief recounting of church services attended and occasional church events; the greater world and its events and characters reaches through and touches the lives of the Minto family.

In 1912, the family living at the Minto homestead included Susie and David J. Minto, daughter Una Jean, and son David Harold and his wife Mildred and their two daughters. (See Diana Dretske's Minto post for a history of the family).

One such diary entry occurred on Monday, August 12, 1912: "Una rec’d her mail today a letter from Jane Addams of the ‘Hull House.’”

Throughout her diary,

Susie Minto (1839-1914) of Antioch/Loon Lake, then in her early 70's, makes mention of

her daughter Una Jean (1876-1963) gathering

flowers from the family’s garden to send to Hull House. They sort and

tie bunches late into the night and box them up to be sent with the milkman on

the earliest Wisconsin Central line train to Chicago.

Jane Addams (1860-1935) was a pioneer in the settlement movement of the late 1800s. Hull-House, opened in 1889 by Addams and Ellen Gates Starr (1859-1940) soon emerged as a vital tool for immigrants, children, and the poor of Chicago. They provided childcare, an art gallery, a library, and classes in English, citizenship, job finding, art, music, and theater.

Susie’s diary entry continues: “[Jane Addams] kindly thanked Una for sending the lovely flowers & said ‘the size of bunches did not really matter although the small bunches such as came yesterday seemed to give particular pleasure to the small children in the Mary Crane Nursery which is housed in one of the Hull House Buildings. The flowers were in splendid condition with much appreciation of your kindly thought of us & the courteous letter, I am sincerely yours.’ The above is a partial copy of letter rec’d by Una [and signed] Jane Addams Aug 12, 1912."

After seeing this routine mentioned numerous times, and after seeing the thank you letter Susie describes, I decided to do a little investigating to find out what the flowers were used for.

I quickly

found some Chicago Tribune articles covering the Hull

House and mentioning flowers for the children. From the Chicago

Tribune on November 1, 1891:

“In the

dining-room is the ‘advanced’ class, absorbed in the mysteries of cutting and

putting together in a logical fashion muslin underclothes. On the sideboard is

a great shining tin dish-pan filled to the brim with marigolds, and geraniums,

and sweet old-fashioned mignonette—an explanation, perhaps, of the presence of

some of these light-hearted, carefree little daughters of Italy, to whom a

whole afternoon of serious application to anything but play must be irksome to

a degree. But all the children love flowers—none more than these.”

The small bouquets in this illustration are similar to the ones Una and Susie Minto had worked so tirelessly to gather and send.

The Tribune article continued:

“And after the sewing is all folded neatly away, the awkward thimble and troublesome needle safely hidden in the depths of the sewing-bag for another seven days; when all the hats and coats have been given to their rightful owners, then that dish-pan is moved out into the hall and every child receives from Miss Addams’ hands a bunch of flowers for her very own. It is worth traveling a long distance just to see this distribution, the joy in it is so evident. With a funny compromise between a bow and a curtsey, a 'thank you, teacher,' and a face wreathed in smiles, each child receives the bit of bloom and fragrance."

After reading Susie Minto’s diary and day after day of chore lists and weather reports, discovering this small glimpse of the larger world as seen through the Minto lens was a beacon of sunlight on an otherwise gray page. It made me start reading closer and looking for even more details connecting these early 20th century rural farmers to larger world events.

Reading old script can be difficult, but by transcribing these diaries the Dunn Museum can make them more accessible to researchers and the general public to enjoy and to make their own discoveries about the past.

~ ~ ~

The Bess Bower Dunn Museum's Minto Family Collection is available online through the host site Illinois Digital Archives.

Friday, January 3, 2014

Passenger Pigeons in Lake County

Passenger pigeon, 1920.

The Orthogenetic Evolution in the Pigeons. Hayashi and Toda (artists) |

The first non-native settlers to Lake County in the mid-1830s found an abundance of wild game, including quail and passenger pigeons. Thousands of pigeons roosted in the county’s oak trees, eating acorns.

Remembrances of those early days were documented by students across Lake County, who in 1918 asked their elders for their memories of the passenger pigeons: In Newport Township, "Wild pigeons... flew in flocks of hundreds and helped furnish the pantry with delicious meat."

"The Passenger Pigeon's Flight to Extinction" exhibition explores connections between the human world and looks at some of the work being done to help prevent similar extinctions from occurring. Lake County Discovery Museum through February 2, 2014.

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

Boxer Gene Tunney Trained Near Lake Villa

|

| Gene Tunney, circa 1928. Online photo |

Tuesday, May 7, 2013

C.R. Childs Real Photo Postcards of Lake County

|

| One of the many stunning postcard views C.R. Childs took in Lake County. This view is of children in a haystack at Selter's Resort, Antioch. Photo taken July 20, 1913. LCDM M-86.1.69 |

|

| A "slice of life" moment captured by C.R. Childs: Wisconsin Central Railroad depot, Antioch, circa 1912. LCDM M-86.1.1 |

It is estimated that Childs, along with the photographers he employed, produced 40,000 to 60,000 different photo postcard views of the Midwest.

|

| Another example of Childs' extraordinary eye for beauty: "Along the Shore at the Toby Inn, Lake Marie, Antioch," circa 1913, by C.R. Childs. LCDM M-86.1.120 |

In addition to the Lake County Discovery Museum, repositories with large C.R. Childs postcard collections include the Chicago History Museum and the Indiana Historical Society.