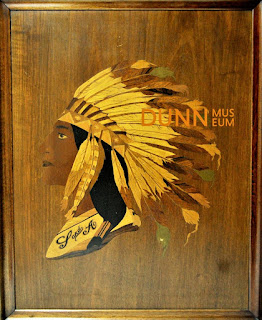

Photo 1950s. Dunn Museum Collections.

Friday, December 17, 2021

Mary Louise Spoor Brand - Children's Book Illustrator

Photo 1950s. Dunn Museum Collections.

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

The Dairy Queen: Grace Garrett Durand

Durand was born in Burlington, Iowa to Martha Rorer and William Garrett. Grace’s ties to the Chicago area likely began with her brother’s marriage to Miss Ada Sawyer in 1884. Ada was the daughter of one Chicago's “pioneer druggists,” Dr. Sidney Sawyer.

In February 1888, Ada Sawyer Garrett and her mother, Elizabeth Sawyer, gave Grace an “elegant reception" at their home. This may have been Grace’s formal introduction to Chicago society. In the following years, Chicago’s Inter Ocean newspaper would note Dr. and Mrs. Sawyers’ travels with Miss Grace Garrett as their guest.

On news of her mother’s declining health, Grace returned home to Iowa to care for her. Martha Garrett died in February 1893.

In April 1894, Grace married wealthy sugar broker, Scott Sloan Durand of Lake Forest. Their wedding was held in Burlington, Iowa “in the presence of a brilliant assemblage of invited guests.” Grace’s maid of honor was the famous watercolor artist and illustrator, Maud Humphrey (1868-1940) of New York. Today, Maud is better known as the mother of Hollywood legend, Humphrey Bogart.

At the turn of the century, Durand shifted her focus to dairy farming as she became aware of infant mortality rates in Chicago linked to contaminated milk. Impure milk was a problem that had been combatted with varying success for centuries, but with the rapid growth of cities the problem was exacerbated. Inspired by her mother’s example of helping others, Grace saw a desperate need to provide clean milk to children.

In 1904, Durand established Crab Tree dairy farm on her Lake Forest property. However, her neighbors were not enamored of having a dairy herd in the neighborhood. Some complained of the “odor and flies” and that the herd’s “bawling” kept them awake at night.

An article in Pearson’s Magazine explained how Grace’s visit to Chicago's “tenement district revealed… most of the infant mortality was due to the want of nourishment, which meant good milk, and that good milk was a rare commodity, difficult to procure, even at exorbitant prices.” Durand used the profits from selling milk and thick cream to Chicago’s most select hotels, restaurants and tea rooms to support needy children.

Durand was known to pamper her cows and referred to them as her "pets." One story noted that she enlisted the unusual method of playing opera music while the cows were milked. Grace supposedly claimed the music made the cows happy and consequently their milk tasted better and was more nutritious.

Dairy operations ceased when Grace Durand died on February 26, 1948. During her lifetime she was recognized as one of the “most powerful leaders in the milk crusade.”

Following Durand's death, William McCormick Blair (1884-1982) and his wife, Helen Bowen Blair (1890-1972), purchased Crab Tree Farm. The Blairs association with Durand had begun in 1926, with the purchase of 11-acres of the farm overlooking Lake Michigan.

Since 1985, Durand’s Crab Tree Farm has been owned by the John H. Bryan family. The property is still a working farm, and the original historic buildings have been renovated and now display collections of American and English Arts and Crafts furniture and decorative arts.

Special thanks to Laurie Stein, Curator at the History Center of Lake Forest-Lake Bluff, for additional research and enthusiasm for this topic.

- Diana Dretske, Curator ddretske@lcfpd.org

Tuesday, November 10, 2020

Women's Army Corps at Fort Sheridan

In September 1939,

Americans were in the tenth year of the Great Depression when war broke out in

Europe with Hitler’s invasion of Poland. As the warfront expanded throughout

Europe and Asia, the U.S. needed to increase the strength of its’ military to

prepare for the possibility of war. These preparations included discussions on

the prospect of a women’s corps.

Along with men, women wanted to do their part to fight the threat of fascism

and many lobbied for a role in the U.S. military mobilization. At the forefront

was U.S. representative Edith Nourse Rogers (1881-1960) of Massachusetts, who

introduced a bill in Congress in early 1941 to establish an auxiliary corps to

fill non-combatant positions in the army.

The bill stalled until the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 propelled

the United States’ into war. Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall,

foresaw a manpower shortage and understood the necessity of women in uniform to

the nation’s defense. Not only were women needed in factories, but also in the

military.

With the support of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and General Marshall, on May

15, 1942, Rogers’s bill (H.R. 4906) passed into law creating the Women’s Army

Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). As an auxiliary unit, the women were limited to

serving with the Army rather than in the

Army.

The purpose of the WAAC was to make “available to the national defense the

knowledge, skill, and special training of the women of the nation."

Women

taking the oath as officer candidates in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps at

army headquarters, Chicago. Four of the women pictured were African American,

including Mildred L. Osby (top left), who would command an African American

Women's Army Corps unit at Fort Sheridan. Chicago Tribune, July 12,

1942.

Of the four hundred and forty women selected for officer candidate training only 40 places were allotted for African American women, reportedly based on “the percentage of the population.” Mildred L. Osby (1913-1953) of Chicago was one of the African American women selected for officer training. Her fellow candidate, Charity Adams Earley, described them as “the ambitious, the patriotic, the adventurous.”

Lt. Mildred L. Osby recruiting women for the WAACs in Washington D.C., November 1942. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

First

WAAC detachment arriving at Fort Sheridan on December 30, 1942. Mary Jane

(Lett) Lucas aka "Jane" is right of center holding large

duffel. Chicago Sun Staff Photo / Fort Sheridan Collection, Dunn Museum

95.32.23.

Among the first detachment of WAACs at Fort Sheridan was Mary Jane (Lett) Lucas (1921-2014), who recalled that the women auxiliaries were given a warm reception. She noted that the army “didn’t know what to do with us,” and was given a job as an usher at the post’s theater. The army quickly figured out how best to utilize the extra "manpower." Duties for the women’s corps included: clerks, stenographers, commissary, photo analysts, surgical assistants, lab assistants, mechanics, and chauffeurs.

On July 3, 1943, the auxiliaries were officially given “active duty status”

with the passing of the bill to create the Women’s Army Corps. All auxiliaries

(WAACs) were offered the choice of an honorable discharge and return to

civilian life or joining the U.S. Army as a member of the Women’s Army Corps

(WAC). Seventy-five percent of the women enlisted.

This new designation was important as it gave women full military rank and

benefits for service injuries and allowed them to serve overseas. It also gave

them protection as soldiers and if captured were eligible for rights given to

prisoners of war.

WAC

Mary Jane (Lett) Lucas, bottom right, with Sixth Service Command Laboratory soldiers and WACs, circa 1944. Lucas met her

husband, Colonel Charles J. Lucas (1923-2011), at Fort Sheridan’s

Non-Commissioned Officers’ club. They married in 1947 and settled in

Grayslake. Mary Jane Lucas Collection, Dunn Museum, 2012.20.39.

Lucas was assigned to the Army’s Sixth Service Command Medical Laboratory at Fort Sheridan, driving officers from the lab, and checking in thousands of samples. This laboratory received more than 66,000 food and water samples from 1941 to 1945. The laboratory’s principal activity was the chemical and bacteriological examination of foods, including large quantities of canned evaporated milk, dried powdered milk, and cheese procured for the Armed Forces. At the lab, Lucas also worked with German prisoners of war, but was not allowed to speak to them.

In November 1943, an African American WAC unit was posted to Fort Sheridan under the command of 1st Lt. Mildred L. Osby (promoted to Captain in January 1944). At the time of her enlistment in July 1942, Osby was married, living in Chicago, and employed at the social security board. She had graduated from Officer Candidate Training at Fort Des Moines, served as a WAAC recruiter in Washington, D.C., posted to Fort Custer, Michigan, and WAC Company B commander at Fort Sheridan.

Capt. Mildred L. Osby, date unknown.

Photo from FindAGrave.com, Arlington National Cemetery.

The seventy-five African American WACs under the command of Capt. Mildred Osby were assigned to duties in the Recruit Reception Center. Soldiers on furlough also passed through the Fort where their service records were checked and instructions given for the length of furlough time they had at home.

Soldiers and WACs worked in the Rotation Section, which had a "graveyard shift" to accommodate the great numbers of soldiers passing through and to "speed overseas veterans through." (The Tower, August 11, 1944).

Twenty-six of the original company of WACs at Fort Sheridan on their two-year roll of honor, December 1944. Mary Jane (Lett) Lucas (top row, red star). Thirty of their WAC comrades had been transferred overseas where they were serving in New Guinea, Egypt, England and France. The Tower, December 29, 1944.

Details of the celebration at Fort Sheridan marking the 2nd anniversary of the creation of the Women's Army Corps. Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1944.

During World War II, nearly 150,000 American women served as soldiers in the Women’s Army Corps. In 1948, for their superb service during the war, President Truman signed the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act allowing a permanent place for women to serve within the military in regular, peacetime forces.

The

Women's Army Corps disbanded in 1978 and all members were fully integrated into

the U.S. Army.

The Dunn Museum is celebrating those who served with a new temporary exhibition Breaking Barriers: Women in the Military through June 13, 2021. To experience this past exhibition, you may view the virtual exhibit online.

- Diana Dretske, Curator ddretske@lcfpd.org

Sources:

Bess Bower Dunn Museum (Fort

Sheridan Collection 92.24/95.23; Mary Jane Lucas Collection 2012.20)

"War Training - First

Contingent of WAACs Arrives at Fort Sheridan," Chicago Daily

Tribune, December 31, 1942.

"Twenty-five WAACs Win

Promotion to Second Officer," Chicago Tribune, January 3,

1943.

"American Women at War - Lt.

Mildred L. Osby," Chicago Tribune, November 28,

1943.

"American Women at War - Capt.

Mildred L. Osby," Chicago Tribune, January 30, 1944.

"WACs at Fort Sheridan to

Observe Anniversary," Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1944.

"'Graveyard Shift' Hastens

Rotation Men Home," The Tower, August

11, 1944.

"WACs Celebrate Second

Anniversary Here," The Tower, December 29, 1944.

"On the Record with Mary Jane

Lucas," Lake County Journal, May 27, 2010.

Earley, Charity Adams. One

Woman's Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WACs. Texas A&M

University Press, 1995.

Treadwell, Mattie E. United

States Army in World War II, Special Studies: Women's Army Auxiliary

Corps. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States

Army, 1991.

Ancestry.com

FindAGrave.com. "Mildred

Lavinia Osby," Arlington National Cemetery.

"Twenty-One Illinois Women Who Are in the Army Now," Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1942.

George C. Marshall Foundation Blog: https://www.marshallfoundation.org/blog/marshall-75th-anniversary-wacs/

The Women’s Army Corps: A

Commemoration of World War II Service, Judith A. Bellafaire

https://history.army.mil/brochures/WAC/WAC.HTM

Thursday, August 5, 2010

Jane Strang McAlister, Millburn