|

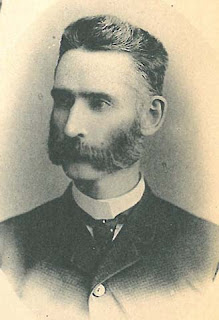

| William Bonner, 1841 - 1863 Courtesy of Bonner Family |

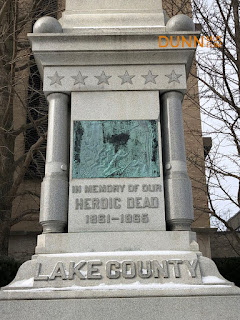

William Bonner Jr. was one of thousands of Lake County men to enlist in the Civil War. By the summer of 1862, the war had become synonymous with death and privation, but Bonner heeded President Lincoln's call to preserve the Union.

Bonner was the eldest child of Scottish immigrants William and Margaret Bonner. In 1842, the family settled along Sand Lake Road south of Millburn (now part of Lindenhurst). Their farm is preserved by the Lake County Forest Preserves as the Bonner Heritage Farm. (See my post on the Bonner Heritage Farm)

|

| William Bonner, Jr. grew up in this house. John Bonner (William's brother) and family, circa 1900. Courtesy of Bonner Family. |

William was born in Canada on the family's trip over from Scotland. He grew up on the Bonner's Avon Township farm (shown above), working as a farmer. He most likely attended the one-room Dodge School (which his father William Sr. built) on the southeast corner of Sand Lake Road and Route 45.

The 21-year old William was recruited by John K. Pollock of Millburn into Company C of the 96th Illinois Regiment. On September 2nd, Bonner went to Waukegan to formally enlist in Pollock's Company. He most likely shared the wagon ride to Waukegan with other neighborhood enlistees, including George C. Dodge, and Henry Bater, a laborer on the Bonner's farm. After several days of training the regiment went by train to Camp Fuller in Rockford, Illinois for more intensive training before heading to the front.

During a portion of his first year of service, Private Bonner suffered from "camp illness." Soldiers were commonly sick due to poor sanitation, poor nutrition, and being exposed to a multitude of diseases. Several letters written by William's comrades in the Dunn Museum's collections note his ill health:

George C. Dodge wrote: "Wm. Bonner don't seem over well now days his legs trouble him considerably." (Letter to David Minto in Millburn, April 17, 1863, from Camp near Franklin, TN - Dunn Museum 93.45.505.2)

"William Bonner has been unwell but is well now he does duty every day," (Letter of Chase Webb to David Minto, May 12, 1863 - Dunn Museum 93.45.519.2)

"William Bonner [is not very well] though he is on duty," (Letter of Captain John K. Pollock to David Minto, May 17, 1863, Franklin, TN - Dunn Museum 93.45.567.2)

The 96th Illinois' first battle came at Chickamauga, Georgia on September 18 - 20, 1863. This battle claimed the second highest number of casualties of the war after Gettysburg. (See my post on Chickamauga)

The 96th Illinois lost half its men in one day's fighting on September 20. Bonner and his comrades of Company C were given a "terrible blow" while defending the Union's position on Horseshoe Ridge. Of the company's 35 men sent into battle, 25 were wounded and the remaining ten had bullet holes through their clothes and accoutrements.

According to the 96th's regimental history, William Bonner Jr. "was shot through the body" in the first charge on Horseshoe Ridge. He was "left upon the field, doubtless dying within a few hours." Bonner did not make it to the field hospital at the rear, but even if he had the wound was fatal.

For many months Bonner's friends and family clung to the hope that he was alive and would be heard from. The Bonners watched the road for any sign of their son's return home.

One of William's comrades, William Lewin of Newport Township, wrote on December 11, 1863, nearly three months after the battle: "I have not seen any one that has seen or heard any thing of Wm Bonner since the battle of Chickamauga." (below)

No news ever came.

|

| Excerpt from William Lewin's letter regarding William Bonner. Dunn Museum 93.45.518.2 |

On the home front, families often never learned the fate of their loved ones. There was no system to identify the dead, notify families, or compensate them for their loss. William Bonner is one of hundreds of thousands of Civil War soldiers who have remained unidentified and their demise unknown.

On Sunday, July 13, 2014 at 10 a.m., the Bonner Family will hold a memorial to honor William Bonner, Jr., whose body was never found. The grave marker (cenotaph) dedication is open to the public and will be at the Millburn Cemetery on Millburn Road east of Route 45.

For a list of Civil War veterans buried at Millburn Cemetery follow this link to the Historic Millburn Community Association website.