Beatrice Pearce (1866 - 1948) was one of the first women doctors in Lake County, and one of the first doctors in the frontier town of Ketchikan, Alaska.

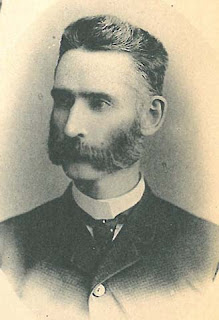

Beatrice Pearce, circa 1899. Dunn Museum, 92.24.294.

In 1847, Beatrice's father, Dr. William S. Pearce, immigrated from England. He settled in Chicago and opened a drug store on N. Clark Street. He married Mary Grace Copp in 1853.

By 1855, Dr. Pearce moved to Waukegan, "Because the ground [in Chicago] was swampy." He re-established his drug store at Genesee and Washington Streets.

After graduating with her medical degree, Beatrice set up her own practice, specializing in diseases of women and children. Her practice was located above the Pearce Drug Store on Genesee Street. She lived with her parents on Julian Street. The Pearce Drug Store was founded by her father in 1855, and later operated by her brother, Dr. William W. Pearce.

|

| Pearce family listings in Waukegan city directory for 1897-1898. Beatrice is shown as a physician and her father W.S. as retired. |

In addition to her medical practice, Beatrice was a suffragette. In March 1897, she attended a Woman Suffrage convention in Waukegan, but the event had low participation due to a blizzard. Still, the women organized a local suffrage association, consisting of 30 members, and Beatrice became its treasurer.

In 1908, Beatrice met Dr. George E. Dickinson, while attending a medical convention in Chicago. They married later that year. Dickinson (1870 - 1956) had immigrated from England and was practicing medicine in Ketchikan, Alaska. He took his new bride to Ketchikan where they practiced together for nearly 40 years.

|

| Postcard of Ketchikan, Alaska, 1918. Curt Teich Co. postcard A74192. |

When Beatrice arrived in Ketchikan, she found a frontier town with a population of approximately 1,600. It was pioneer country compared to the bustle of Waukegan with a population of 16,000, in addition to the nearby metropolis of Chicago. Ketchikan got its start in 1883 with the establishment of salmon fishing and canning, and later mining and timber companies. Today, it's known as the Salmon Capital of the World, and salmon and tourism are the foundation of the local economy.

Beatrice and George had no children. They devoted their lives to the well-being of the residents of Ketchikan.

Beatrice passed away March 16, 1948 and is buried in Bayview Cemetery, Ketchikan. Memorial services were held in Waukegan on April 1, 1948, and conducted in the Masonic temple by the Waukegan chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star, to which Beatrice had belonged since 1892.

Beatrice and George had no children. They devoted their lives to the well-being of the residents of Ketchikan.

Beatrice passed away March 16, 1948 and is buried in Bayview Cemetery, Ketchikan. Memorial services were held in Waukegan on April 1, 1948, and conducted in the Masonic temple by the Waukegan chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star, to which Beatrice had belonged since 1892.

- Diana Dretske, Curator ddretske@lcfpd.org

Sources:

Lake County History Archives/Bess Bower Dunn Museum.

Curt Teich Postcard Archives.

Lake County History Archives/Bess Bower Dunn Museum.

Curt Teich Postcard Archives.

"Woman Suffrage Work at Waukegan," Chicago Tribune March 24, 1897.

Waukegan City Directory 1897-98, Vol. II, Whitney Publishing Co., Chicago, Illinois.

"Dr. B.P. Dickinson Memorial Rites Will Be Conducted April 1," Chicago Tribune March 25, 1948.

"Dr. Dickinson Dies in Alaska," Waukegan News-Sun, 1948.

"Waukegan: A History" by Ed Link, Waukegan Historical Society, 2009.

Mommd.com - MomMD is a leading online magazine, community and association for women in medicine.

"Waukegan: A History" by Ed Link, Waukegan Historical Society, 2009.

Mommd.com - MomMD is a leading online magazine, community and association for women in medicine.

Census records

Family records on Ancestry.com

.jpg)