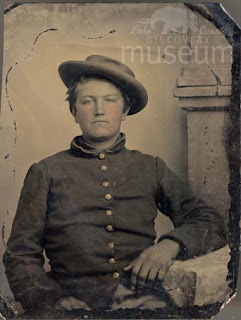

Photo of Captain A.Z. Blodgett from the History of the 96th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, 1887.

Asiel Z. Blodgett was born at Fort Dearborn (Chicago) in 1832. As a young man, he became an employee of the Chicago & North Western Railroad Company, and in 1858, he was made the station agent at Waukegan. His older brother, Henry Blodgett, was the abolitionist and judge mentioned in several previous posts.

Asiel served as station agent until July 1862, when he received a recruiting commission from Governor Yates, and according to the regimental history: "with the cooperation of leading citizens and businessmen, undertook the work of enrolling a sufficient number of men to form a Company." He was promoted to Captain of Company D of the 96th Illinois on August 9.

During one of the initial skirmishes of the Battle of Chickamauga, on September 18, 1863, Blodgett received a severe gunshot wound in the right shoulder near McAfee Church while advancing the skirmish line. He did not leave command and fought with the regiment until Sunday, September 20, when he was disabled by a heavy tree limb that was torn off by artillery fire and fell on him, injuring his back.

According to his biographical sketch of 1891, Blodgett participated in all engagements of the Atlanta campaign and was with General Sherman until the capture of Atlanta. He was also present at the Battle of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge.

On returning to Waukegan after the war, Blodgett resumed his position as station agent, where he worked until his retirement in 1900. He was recognized as the oldest employee of the railroad at Waukegan, having been with the company for 42 years, except during his service in the Civil War. He was considered "prompt, correct and reliable and by his uniform courtesy and fairness has won the respect and good will of all with whom he has had business relations."

In addition to this full-time position, in 1875, he began dealing in fine horses and cattle, being a proprietor of a stock farm situated several miles outside of the city where he bred Clydesdale horses and Galloway cattle. He served two terms as the Mayor of Waukegan (1883 and 1884).

Asiel died in 1916.

Asiel served as station agent until July 1862, when he received a recruiting commission from Governor Yates, and according to the regimental history: "with the cooperation of leading citizens and businessmen, undertook the work of enrolling a sufficient number of men to form a Company." He was promoted to Captain of Company D of the 96th Illinois on August 9.

Postcard of McFarland's Gap, Battle of Chickamauga, Georgia. Curt Teich Co. RC411.

During one of the initial skirmishes of the Battle of Chickamauga, on September 18, 1863, Blodgett received a severe gunshot wound in the right shoulder near McAfee Church while advancing the skirmish line. He did not leave command and fought with the regiment until Sunday, September 20, when he was disabled by a heavy tree limb that was torn off by artillery fire and fell on him, injuring his back.

According to his biographical sketch of 1891, Blodgett participated in all engagements of the Atlanta campaign and was with General Sherman until the capture of Atlanta. He was also present at the Battle of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge.

Blodgett from a glass negative, circa 1878. Dunn Museum 2011.0.86

In addition to this full-time position, in 1875, he began dealing in fine horses and cattle, being a proprietor of a stock farm situated several miles outside of the city where he bred Clydesdale horses and Galloway cattle. He served two terms as the Mayor of Waukegan (1883 and 1884).

Asiel died in 1916.