Lake County had its share of mineral springs inland from Lake Michigan. The natural artesian springs bubbled to the surface of the land. Investors had the water analyzed and then advertised it as a "water cure." Even Besley's Waukegan Brewery, which used water from a local spring, claimed that the water gave its brew curative properties.

In Waukegan there were four springs—Glen Flora, McAllister (aka Quintette), Magnesia, and Sag-au-Nash.

The Glen Flora Springs was probably the best known. It was located in the Glen Flora Ravine east of Sheridan Road on the property of Calvin C. Parks (1805-1860). A hotel was built on the east side of Sheridan Road to accommodate tourists coming to enjoy the spring.

Dedication day at Glen Flora Springs, 1874. The two men at front left are holding glasses of water. Notice the funnels next to the spring's hole for easy pouring into bottles. Dunn Museum 92.32.264.

Advertisement for Glen Flora Springs boasting "no more sewage in your drinking water." July 7, 1900 Waukegan Daily Sun. www.newspapers.com

The McAllister Springs were originally called Quintette Springs. This spring was owned by Judge McAllister, and located south of Belvidere Road and west of McAllister Avenue in the present Roosevelt Park.

The Sag-au-Nash Spring was owned and operated by Elijah M. Haines. The spring's location was south of the Waukegan River in the central part of the city.

The letters of an unidentified woman traveling by rail in 1881 were published by the Chicago and Northwestern Railway Company under the title, "My Rambles in the Enchanted Summer Land." The letters testify to the beauty and value of these springs. She wrote that Waukegan's springs: "attract hundreds of summer visitors who desire rest and healthful amusement, together with the benefit derived from its valuable mineral water."

Of her visit of the Glen Flora Springs she wrote: "They were nestled lovingly in a romantic glen, the sunlight sifting through the trees..."

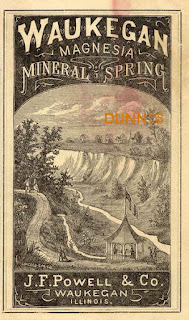

She also visited the Magnesia Mineral Springs, which are referred to as "Powell's water" for its owner J.F. Powell. The Magnesia Springs were located on Glenrock Avenue between Bluff and Lincoln.

The traveler wrote that Magnesia Springs "has effected many remarkable cures, which are so astonishing, yet perfectly reliable, that their repetition savors strongly of the 'legendary.'"

What became of Waukegan's springs and also those in Libertyville (Abana Springs) and Highland Park (Sparkling Springs)? Simply put, people pressure. The demand for water use through residential and industrial development depleted the water level of the springs to the point where they no longer bubbled to the surface.

As far as I know, the only spring still in operation is Highland Park's Sparkling Spring Water Company. When it was founded in 1896 by William Tillman, the water gushed out so forcefully it was called "sparkling spring" for the way it jumped in the sunlight.

Like other local springs, the McAllister Spring was landscaped to give it a park-like setting. The site would become Roosevelt Park, Waukegan Park District. Dunn Museum.

The letters of an unidentified woman traveling by rail in 1881 were published by the Chicago and Northwestern Railway Company under the title, "My Rambles in the Enchanted Summer Land." The letters testify to the beauty and value of these springs. She wrote that Waukegan's springs: "attract hundreds of summer visitors who desire rest and healthful amusement, together with the benefit derived from its valuable mineral water."

Of her visit of the Glen Flora Springs she wrote: "They were nestled lovingly in a romantic glen, the sunlight sifting through the trees..."

She also visited the Magnesia Mineral Springs, which are referred to as "Powell's water" for its owner J.F. Powell. The Magnesia Springs were located on Glenrock Avenue between Bluff and Lincoln.

Magnesia Springs with its beautiful gazebo. Dunn Museum.

Magnesia Springs brochure, which includes the springs' mineral content, 1875. Dunn Museum 2007.3.7.

Magnesia Spring advertisement, circa 1875. Dunn Museum2007.3.6

Advertisement for Glen Flora Mineral Springs showing an analysis of its water, 1874.

What became of Waukegan's springs and also those in Libertyville (Abana Springs) and Highland Park (Sparkling Springs)? Simply put, people pressure. The demand for water use through residential and industrial development depleted the water level of the springs to the point where they no longer bubbled to the surface.

As far as I know, the only spring still in operation is Highland Park's Sparkling Spring Water Company. When it was founded in 1896 by William Tillman, the water gushed out so forcefully it was called "sparkling spring" for the way it jumped in the sunlight.